The understanding of the tame problem space may lead to some clues how to start thinking about the wicked problem space

The Scientific Revolution has its roots back to the 16th and 17th centuries where science became a distinct discipline from philosophy and technology. The view of nature became one of a machine rather than an organism, and the beginnings of formal experimentation and the scientific method. Present-day scientific knowledge and tools, enabled with technology, have eclipsed what was understood at the birth of the Scientific Revolution. With the scientific methodology being credited in large part with the success of the empiricism of science over the frail human emotions of irrational beliefs and superstition. This is the universe of discourse where problems of inquiry have been tamed by the scientific methodology, we no longer believe that the Greek god Helios pulls the sun across the sky with his golden chariot.

Due to the long history of the natural sciences and the scientific methodology and its taming of the universe, can anything be gained by examining its status and usage for lessons which could be applied to the relatively young concept of wicked problems? There is a division between the natural sciences and the social sciences which could be said to mimic the division between tame problems and wicked problems, and the application of the scientific methodology and its empirical basis is perceived as the undisputed path to the truth of the universe. It is contented that this division is not as clear and distinctive as imagined and having simplistic understanding of the natural sciences and the use of the scientific methodology may actually impede expectations and progress of dealing with wicked problems!

What is Science

There are many general descriptions of what science means, for example:

- Knowledge about or study of the natural world based on facts learned through experiments and observation. (Merriam-Webster)

- Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence. (Science Council)

Within any definition of science resides the concept of a scientific methodology that filters out opinions, hearsay or myth to obtain scientific facts which cannot be disputed. That’s the simplistic interpretation which hides the true extent of science and the scientific methodology. Much like the visible portion of an iceberg floating in an ocean requires diving deep below the surface to see the true size and extent of the iceberg.

The Scientific Method

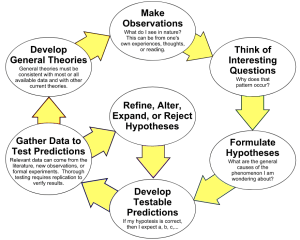

The scientific method for problem solving typically consists of the following basic steps. Many variants of this list exist they are effectively the same:

- Observe a phenomenon that requires explanation

- Ask pertinent question about the phenomenon

- Form a testable hypothesis that allows predictions to be made

- Test the hypothesis in an experiment

- Analyze the test results and predictions; accept or reject the hypothesis or modify the hypothesis

- Repeat the test until the predictions and test results are identical

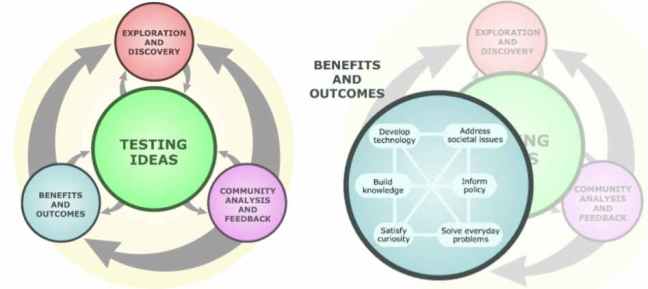

Many diagrammatic representations exist of the scientific methodology as depicted below:

An interactive website exploration of How science works: The flowchart provides a much more nuanced concept of science. For example, selecting the Benefits And Outcomes balloon figure 2a gives greater detail as shown in figure 2b, subsequently selecting one of the balloons (i.e., Build knowledge) opens a page related to the topic. This is a large step forward in describing science to school children or lay people to conceptually understand science at a high level.

The scientific method is generally considered to be at the core of advances in scientific knowledge and if followed, was guaranteed to produce results. That if used, can and will solve all sorts of problems given sufficient time and resources. The problem being: except for the most straightforward situations offering clear cause-and-effect relationships, the notion that here is a routine for automatically solving any scientific problem is patently false. (Shamos, 1995) The purpose of articulating a scientific methodology was not to follow verbatim as a recipe for scientists, rather as a guide for students on how scientists practice their discipline. It also forms part of science communication to inform the public that scientific knowledge is built upon a reliable and sound methodology.

A research paper by Wong and Hodson questioned scientists from different disciplines to describe their actual practice of doing science in their profession, in summary: The descriptions of their practices provide a somewhat striking contrast to the image of science usually portrayed in science curricula and textbooks. (Wong and Hodson 2009) Two quotes in particular capture the essence of doing science:

All scientists in our study stated that creativity and imagination are important at all stages of an investigation (planning and designing; data collection; data interpretation), though the nature and extent of creativity and imagination may vary between stages.

. . . the need for two kinds of scientists: those whose strengths lie in rigorously and logically applying what we regard as secure knowledge to generate accurate and reliable data, and those with “researcher wisdom,” who are flexible and unrestrained in their thinking and “who do things no-one else would have considered.”

Creativity and imagination do not appear in any description of the scientific methodology and a recalcitrant scientist daring to do things no-one would have considered appears blasphemous. These aspects are strangely missing from any variant of the scientific methodology.

Other researchers have investigated the effect of concentrating on the scientific methodology as discrete steps in a classroom setting, how it affects students’ inquiry and teachers’ perceptions.

- the scientific method, when viewed as rigid, decomposable steps, not only contributes little to scaffolding inquiry but can also distract students and teacher away from attending to productive scientific inquiry

- when students pursue authentic scientific questions, the hypotheses and tests they develop can contribute to their investigations without necessarily obeying the requirements of “the” scientific method. (Tang 2010)

While some authors are not so diplomatic in their critique of the scientific method being sacrosanct. But to squeeze a diverse set of practices that span cultural anthropology, paleobotany, and theoretical physics into a handful of steps is an inevitable distortion and, to be blunt, displays a serious poverty of imagination. . . . Educators, scientists, advertisers, popularizers, and journalists have all appealed to it. Its invocation has become routine in debates about topics that draw lay attention, from global warming to intelligent design. Standard formulations of the scientific method are important only insofar as nonscientists believe in them. (Thur 2015)

A realistic analogy is given by Max Born a Nobel Prize winning Physicist I believe that there is no philosophical highroad in science, with epistemological signposts. No, we are in a jungle and find our way by trial and error, building our road behind us as we proceed. We do not find signposts at crossroads, but our own scouts erect them, to help the rest. (Born, 1943) This depicts scientists, particularly at the leading edge as explorers using the available tools on hand that is appropriate for the terrain being covered. Rather than follow a simplistic recipe, they are required to use prior knowledge of the terrain already traversed and of how to use the available tools at the appropriate time. An explorer may use a map, compass, climbing ropes, machete and binoculars to make their way through unexplored lands. A scientist uses mathematics, logic, scientific equipment to carry out experiments or observations, and build upon scientific knowledge already gained throughout history. On top of that the scientist makes use of imagination, creativity and wisdom to know what to use and when, it is this aspect that separates the leading edge scientist who displays originality from a cookie cutter technician following a recipe!

The typical explorer wondering around strange and exotic lands with the chance of being lost, fatally injured, starving, dying of exposure or attacked by man or beast would want to be aware of what they were getting themselves into. Is the new country mountainous, have many river crossings, arid desert, torrential rain, available wildlife for food, inhabited by equally hungry natives or beasts. There are numerous questions to ask to prepare for such a journey and some questions may not have an answer until the explorers boot makes contact with terra firma. Once on the ground the explorer comes across the unexpected and is left to his/her wits, gut feel, intuition to find a way around or cope with.

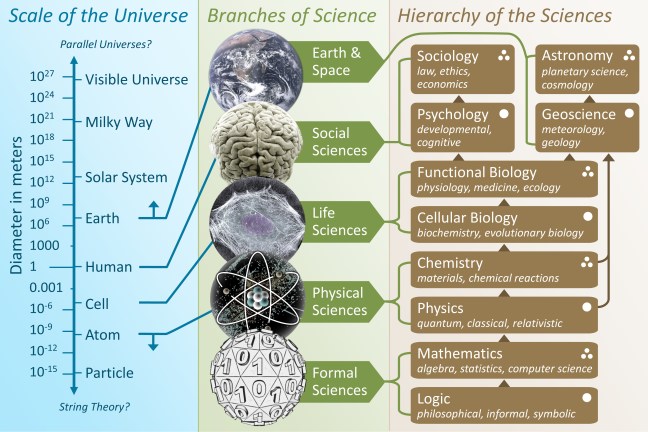

To give an idea of the multitude of terrains an intrepid scientist may explore is illustrated by the sample of disciplines and sub-disciplines of science as given in figure 3. It is easy to imagine the differences in scientific knowledge and tools required for each of theses disciplines. Note that the discussion regarding the Scientific Methodology as typically presented is focused on the Natural Sciences. The Social Sciences may use aspects of the Formal Sciences, for example statistics, but historically there has been and continues to be some antagonism between the objective Natural Sciences versus the subjective Social Sciences. This simplistic dichotomy will be shown to be false!!

Pushing the boundaries

Performing an experiment in say classical mechanics in a laboratory is easy to visualize. The scientist changing some conditions; run the experiment multiple time; measure of log the result. This fits reasonably close to the scientific methodology as published. To perform a repeatable experiment when studying black holes in cosmology is not possible; or the concept of supersymmetry in particle physics faces problems as has been identified:

This year, debates in physics circles took a worrying turn. Faced with difficulties in applying fundamental theories to the observed Universe, some researchers called for a change in how theoretical physics is done.

. . . theoretical physics risks becoming a no-man’s land between mathematics, physics and philosophy that does not truly meet the requirements of any.

What to do about it? Physicists, philosophers and other scientists should hammer out a new narrative for the scientific method that can deal with the scope of modern physics. (Ellis and Silk 2014)

In a response piece to the above:

. . . experimental confirmation being the very heart of science. But a growing controversy at the frontiers of physics and cosmology suggests that the situation is not so simple.

Today, our most ambitious science can seem at odds with the empirical methodology that has historically given the field its credibility. (Frank and Gleiser 2015)

Cosmology and theoretical physics may be argued as extremes of scientific inquiry from the infinitely large scale measured in light years to the infinitesimally small scale as depicted in figure 6 below. But scientific inquiry is digging ever deeper in many if not all of the natural sciences.

The experiments/observations that are made by any discipline in the natural sciences is also limited by cost or access to equipment; qualified personal; or time restraints. Typically any scientist does not have unlimited access to time and resources. Any discipline of the natural sciences is also subjected to continual improvements in testing and measuring equipment or improved procedures giving more accurate results or insights.

Tools of Science

In figure 3, disciplines such as Mathematics and Statistics are listed as a Formal Science in their own right, they are also used as tools in most of the other sciences. In the same manner that Optics is a discipline of Physics it also contributes to the technology of creating better quality optics that other sciences use in the way of telescopes, microscopes, cameras and many other measuring instrumentation. While an Applied Science such as Computer Science is used to assist in all the other sciences, for example modelling of meteorological events using updated mathematical models and artificial intelligence on a supercomputer. The sciences and technologies required to build a particle accelerator used in the study of particle physics would include numerous sub-disciplines from Physics and Chemistry. Therefore there is a complex and intricate web of sciences and technologies helping to expand our knowledge in other disciplines of science.

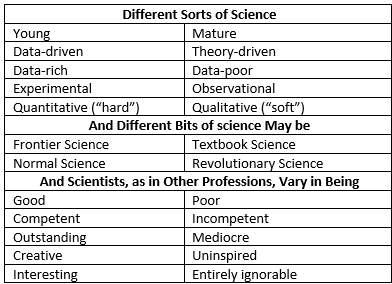

Other aspects of how to view science relates to the maturity of the discipline (see figure 4). Physics as a general discipline is the most mature of the sciences, however sub disciplines vary considerably. Classical mechanics includes Newton’s Laws of motion whereas modern physics include particle physics or quantum physics are what Bauer would label young. One aspect that Bauer also includes in his study of science is that of the scientist. This becomes more important on realization the part that imagination, creativity and wisdom play. Whilst another aspect missing from Bauer’s list are resources, which could include:

- adequate research funding whether privately or publicly sourced

- profile of the discipline where particular research streams may attract more people to join the ranks if it is deemed high profile, greater possibility to contribute and be acknowledged, or improve ones resume

- an area that is perceived to have value to humanity or the environment in some way

Another interesting view on science given by Bauer is one of a Knowledge Filter as shown in figure 5. Note that it progresses from the unreliable subjective to the reliable objective which only helps to reinforce the distinction between the rational and objective natural sciences by filtering out and removing those rebellious human traits of misguided subjective thinking.

Scale of science

Branches of science can also be represented dependent upon the scale of its investigation as illustrated in figure 6.

Fields on Knowledge

Robert J. Sternberg is a Professor of Human Development whose research includes but not limited to intelligence, creativity, and wisdom wrote that fields of knowledge go through a series of overlapping periods:

- an initial stage in which people become interested in a phenomenon and start thinking about how to study it;

- an early developmental stage in which theory and research really get going and people try to set paradigms and convince others of the worth of their paradigms;

- a mature stage in which one or more of a small number of paradigms become prominent while others wither on the vine, and a bevy of researchers further develop those paradigms that have passed the early stages;

- and a postmature stage in which researchers become frustrated with inconsistencies in experimental results and with the inability of the going paradigm or paradigms to answer the questions they really want to answer. (Sternberg 1990)

The question would be at what period does the concept of wicked problems currently hold!

No single Science or Scientific Methodology

The exercise above was not to present a complete discussion regarding the understanding of what is science or the scientific methodology, rather to illustrate the diversity and nuances of what it means to “do” science. For each discipline and sub-discipline of science has its own unique set of methods, background knowledge, language, and epistemic belief. It is also important to note that scientists themselves are human beings working in a competitive environment for recognition and resources. Regardless of how one looks at “science” it has many faces depending on the context and motivations of the people involved in the pursuit of “knowledge”.

Consider a simple concept of a map. There are multiple types of maps available depending on the information the person seeks which could grained from a topographic map, geologic map, political map, physical map, road map, cadaster map and many more. The simple map at a public transport hub indicating train lines and stations is not drawn to scale and is used to indicate the order of train stations on different lines. When considering the placement of a new dam for water storage, various maps would be used such as topographical for natural valleys and waterways; average rainfall; geologic map to ensure stability of dam wall and seepage; road map to determine what roads or tracks may be subjected to flooding and possibly building a new road to transport heavy machinery on. The correct map is chosen for the required information and context.

Paul Feyerabend a philosopher of science highlighted events such as the wars in Yugoslavia and advances made in the theory of the Big Bang and then posed the question:

On one side there is a great and exciting discovery, affecting, so it seems, all of humankind. On the other side war, murder, cruelty. Is there a connection? Is there a way of making sense of both? Is there a way of using the products of our curiosity and our intelligence to influence, attenuate, redirect our base instincts? (Feyerabend 2011)

He continues:

. . . scientists, warlords, the hungry and the rich – they all are human beings. If we want to understand what is going on and if we want to change what displeases us then we have to know the nature of the world and of human beings and we also have to know how they fit together. . . . There is one world, we all live in it, so we had better learn how things hang together.

How are the natural sciences depicted?

There is no single representation that could depict the natural sciences and their characteristics leading to an understanding of how science in conducted or problems are solved. Rather it is the fact that many maps may be required depending on the researchers or analysts requirements and this may vary significantly dependent not only on the discipline, but also the sub-discipline and sub-sub-discipline!!! The above presentation only outlined a couple of categories or maps, while there is no reason to assume that the maps are two dimensional or that the dimensions are fixed.

Tame or wicked problem space

Many researchers have presented the concept of wicked problems in contrast to tame problems. Rittel & Weber’s original list of ten traits of wicked problems highlighted how they are different to the tame scientific methodology. This stark contrast hides that it is not a binary choice between wicked or tame, rather a nuanced situation as identified by Alford & Head and others. In combination with Sternberg’s observation that knowledge experiences its own periods could be applicable not only to researchers in any specific field, but extended to the general public. A recent and obvious example of this being COVID-19 vaccinations. The research and development in this sphere was compressed to quickly bring a vaccine to the market, which the general public was somewhat hesitant to receive. As time progressed and more people became vaccinated; the concern of blood clots with AstraZeneca vaccine; various protests worldwide against mandates for masks, vaccines or lock-downs; the situation has changed with some people becoming comfortable with receiving the vaccination even if the conspiracy theories on social media continues to muddy the waters. One could imagine that the situation would become no more controversial than the typical flu vaccine, noting that there will always be some level of anti-vaxers. In this case of COVID-19, the periods of knowledge are not only in the area of medical science and vaccinations, it includes the general public’s knowledge of risks and safety regarding COVID-19.

This is not a recent phenomena as history of technology and it’s introduction into society is replete with stories of slow acceptance of technology whilst technology itself is undergoing considerable improvements. Consider the history of passenger flights where many people would have been hesitant to get into one of those flying contraptions (even if they could afford it). Airline technology and safety has advanced many fold since the early days, but it would still be possible to find some people who hate to fly or simply would choose not to.

References

- Archon Magnus, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Bauer, Henry H. 1992. Scientific Literacy and the Myth of the Scientific Methodology. University of Illinois Press

- Born, Max. 1943. Experiment and Theory in Physics. Dover Publications

- Ellis, George, and Joe Silk. 2014. “Defend the integrity of physics.” Nature 516: 321-323.

- Feyerabend, Paul. 2011. The Tyranny of Science. Polity Press

- Frank, Adam, and Marcelo Gleiser. 2015. “A Crisis at the Edge of Physics.” The New York Times, 5 June. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/opinion/a-crisis-at-the-edge-of-physics.html.

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Science. Retrieved from Online dictionary: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/science

- Science Council. (n.d.). Our definition of science. Retrieved from https://sciencecouncil.org/about-science/our-definition-of-science/

- Shamos, Morris H. 1995. The Myth of Scientific Literacy. Rutgers University Press

- Sternberg, Robert J., ed. 1990. Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. Cambridge University Press

- Tang, X., Coffey, J.E., Elby, A. and Levin, D.M. 2010. “he scientific method and scientific inquiry: Tensions in teaching and learning.” Science Education 94 (1): 29-47

- Thur, Daniel P. 2015. “Myth 26 That the Scientific Methodology Accurately Refects What Scientists Actually Do.” In Newton’s Apple and Other Myths About Science, edited by Ronald L. Numbers and Kostas Kampourakis. Harvard University Press

- University of California Museum of Paleontology. (n.d.). Understanding Science: How Science Really Works. Retrieved from https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/scienceflowchart

- Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). The Scientific Universe. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Scientific_Universe.png

- Wong, S.L, and D Hodson. 2009. “From the horse’s mouth: What scientists say about scientific investigation and scientific knowledge.” Science Education 93 (1): 109-130